Comment on this article

Your Cliff’s Notes on Yale School of Medicine

Some lofty heights, and a few ignominious lows, of 200 years of medical education

November/December 2010

by the Editors

Two centuries ago, Connecticut chartered a medical school at Yale. Ever since, through lean times and good times, the school has been training future doctors and, especially in its second century, performing signal medical research.

For this modest selection of highlights, we’ve drawn from many sources. Not all of Yale University’s contributions to medical science appear here, because not all took place at the medical school; for instance, it was a zoology professor and a postdoc who helped launch the era of genetic testing in 1980 by producing the first strain of transgenic mice. Nor can all of the medical school’s own history, scientific or otherwise, be compressed into one magazine article.

You can read more in the new official history, Medicine at Yale, by Kerry Falvey. Or you can attend one of the 2010–11 bicentennial events listed on the school’s website, medicine.yale.edu. If you do, read this timeline first: it should get you through a cocktail party or two.

1806

Yale’s board of trustees resolves that Yale should hire a professor of medicine. This obvious step toward establishing a medical school attracts the keen interest of the Connecticut Medical Society, which up until now has enjoyed a monopoly on granting medical degrees in the state. Extended negotiations begin.

1810

Yale and the medical society agree on terms for a joint venture. The medical school, sixth in the country, is chartered by the Connecticut legislature.

1813

The school opens for business, with 37 students. Its five professors range from the nationally known chemist Benjamin Silliman '96 to the Connecticut physician Eneas Munson '53, an alchemist by hobby. (Munson, 79, evidently has an honorary post; he will never actually do any teaching.)

1824

1824 riot |

A West Haven farmer discovers that the grave of his 19-year-old daughter is empty. He demands to search the medical school and finds her body hidden in the cellar. Rumors were already circulating in town that medical students had dug a tunnel from the school to the Grove Street Cemetery across the street, and the news of the grave robbery sparks a week-long riot, town against gown. Eventually, the state legislature will ease the severe shortage of cadavers for medical schools by permitting dissection of the bodies of executed criminals.

1835

The school starts optional spring and summer demonstration courses—unusual in an era when most medical schools attracted students by offering lecture classes and low standards, and medical societies (including Connecticut's) granted licenses to students who had just a year of medical instruction.

1839

Yale requires all MD candidates to complete a thesis demonstrating wide reading in medical literature. Except for a brief hiatus, the thesis requirement will remain in place. (Today, students must do original research.)

1857

Cortlandt Van Rensselaer Creed earns his Yale MD, becoming the first African American to receive a Yale degree. (The first African American to earn a U.S. MD received his in 1847 from Rush Medical College.) Creed will set up a successful practice in New Haven and later serve in the Civil War as acting surgeon of the Thirtieth Connecticut Colored Regiment.

1873

The medical faculty complains to Yale’s trustees that the school is in “critical condition” due to inadequate funding. Professors are reduced to covering expenses out of their own pockets.

1879

Yale starts requiring medical school applicants who lack college degrees to take an entrance exam. (The only other school in the northeast to do so is Harvard.) With the entering class of 1881, new enrollment drops to its lowest point ever: 21 students.

1901

William H. Welch '70, first dean of the preeminent Johns Hopkins medical school, is asked to speak at Yale on “the relation of Yale to medicine.” He complains in a letter to his sister: “If they had only asked me to talk on the relation of Yale to Calvinism or football there would be something to say.” In the talk, he will urge the university to provide more funding.

1910

A Carnegie Foundation investigator evaluates 155 U.S. medical schools and deems only 31 worth keeping. Yale’s and Harvard’s are among them, the only two in the northeast. But the report delivers a withering assessment of Yale: although the medical school requires entering students to have at least two years of college, it does not “deserve the higher-grade student body” because, as with many U.S. medical schools, its curriculum is more suited to high school graduates. The report calls for “larger permanent endowment.” Yale begins to raise more money for the school.

1913

Yale and New Haven Hospital (now Yale–New Haven Hospital) agree to collaborate on turning the hospital into Yale’s primary teaching hospital.

1915

The school’s Department of Public Health is founded.

1916

Louise Farnam |

Sixty-seven years after New York’s Geneva Medical College granted the first U.S. MD for a woman, three women—Louise Farnam, Helen May Scoville, and Lillian Lydia Nye—are admitted to Yale School of Medicine. (Their admission is contingent on Farnam’s father donating $1,000 for a women’s bathroom.) Farnam will graduate first in her class and later teach and practice for ten years in China.

1920

The Yale trustees recognize the “obligation of the University to Medical Education”—and to the funding of medical education—and resolve that the medical school should be developed into “an institution… of the highest type.” In the same year, Milton C. Winternitz, the school’s first full-time Jewish professor, is appointed its fifth dean. He will stay in office until 1935 and today is generally credited with realizing the trustees' ambition for an outstanding medical school. Winternitz—whom Yale president James R. Angell calls a “steam engine in pants”—will recruit eminent faculty, restructure the curriculum, raise funding, and oversee the design of Sterling Hall of Medicine.

1933

Harvey Cushing |

Harvey Cushing '91, a celebrated neurosurgeon, leaves Harvard after reaching mandatory retirement age and joins the Yale medical faculty. He will bequeath Yale two extraordinary collections: his rare medical books and his brain tumor specimens. (Yale has recently established a mini-museum for the tumor collection.)

1935

John F. Fulton, a physiologist and author of a major neurology textbook, invents the lobotomy. Fulton performed the procedure in a lab experiment on chimpanzees, but other neuroscientists will use it to calm human mental patients. In 1951, Fulton estimates that 20,000 patients have been lobotomized. He recommends modifying the procedure to do less damage, but says it is often “indicated and justified.” However, the operation becomes increasingly controversial due to its widely varying results, especially after Rosemary Kennedy’s family reveals in 1962 that she was permanently institutionalized after a lobotomy.

1942

Anne S. Miller |

The first trial of penicillin in the United States takes place at New Haven Hospital (later Yale–New Haven Hospital). When Anne S. Miller, wife of Yale’s athletic director, lay dying of an infection, her doctor asked neurologist John Fulton to use his connections with British scientists to get some penicillin. Fulton procured some of the first doses manufactured in the United States. Miller’s fever drops and her life is saved.

1942

Two pharmacologists doing classified research on chemical weapons for the military notice that the compound they are studying kills lymph cells and white blood cells faster than other cells. Could these nitrogen mustards, Louis S. Goodman and Alfred Gilman wonder, be used against lymphoma? In tests in mice and a terminally ill cancer patient, the compound successfully shrinks tumors (though the patient’s advanced cancer returns). When the war ends and the research is declassified, the new cancer treatment of chemotherapy is introduced to the world.

1946

Pediatrician and psychiatrist Edith B. Jackson creates one of the first “rooming-in” arrangements in a hospital, in which new mothers can have their infants by their beds whenever they want.

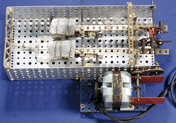

1949

For his MD thesis, William H. Sewell Jr. '49MD builds the first prototype of a pump to route a patient’s blood around the heart and to the lungs, so as to allow open-heart surgery. He and his adviser use it to conduct successful open-heart surgery on a dog. The prototype, including a motor made with an Erector Set, is now in the Smithsonian.

1952

Researcher Dorothy Horstmann proves that the polio virus reaches the central nervous system via the blood, overturning the accepted theory that the virus grew solely in nerve cells. Horstmann’s discovery will be crucial to the development of the polio vaccine. (In 1969, she will become the first woman in the university to receive an endowed professorship.)

1957

Orvan W. Hess and Edward H. Hon, both of the ob-gyn department, design the first device for continually monitoring the fetal heartbeat during labor.

1961

Ob-gyn department chair C. Lee Buxton and the medical director of a local Planned Parenthood clinic test the constitutionality of the Connecticut law against birth control by providing contraceptives to a married couple. After their arrest, they appeal the conviction. The 1965 Supreme Court ruling on the case, Griswold v. Connecticut, will void the state laws against contraception for married couples that were then on the books in some 30 states.

1966

Gynecology professor John McLean Morris and Gertrude van Wagenen, an endocrinologist in the ob-gyn department, develop the “morning after” pill, which prevents a fertilized egg from implanting in the uterus.

1968

Psychiatrist James Comer begins developing the “Comer model” for improving underachieving elementary schools by incorporating ways for schools to address children’s developmental and social needs; it is used today in more than a thousand schools in 26 states. (In 1975, he will become the first African American to earn tenure in the medical school as a full professor.)

1973

As part of the U.S. “war on cancer,” the National Cancer Institute designates the nation’s first eight Comprehensive Cancer Centers, where advanced diagnostic and treatment methods will be developed and demonstrated. Yale is among them.

1975

Professor of medicine Stephen E. Malawista and research fellow Allen C. Steere determine that the cluster of mysterious symptoms affecting children in the area of Lyme, Connecticut, is a tick-borne bacterial infection. They name it Lyme disease.

1978

The FDA approves the first effective new glaucoma treatment since the 1900s, developed by ophthalmologist Marvin L. Sears and still in use today.

1979

Pediatrics professor William V. Tamborlane and professor of medicine Robert S. Sherwin design the first insulin infusion pump for diabetics. The device, an early version of the pumps now used by some 200,000 patients in the United States, provides small doses of insulin continuously around the clock, replacing the difficult process of injecting oneself several times a day—and significantly reducing the bloodstream spikes in insulin and sugar that damage the body over time.

1988

Geneticist Arthur L. Horwich discovers one of the crucial mechanisms involved when proteins in the body fold and misfold. The finding opens new routes for research to prevent or treat Lou Gehrig’s disease, Alzheimer's, and other devastating neurodegenerative diseases.

1989

Immunologist Charles Janeway Jr. develops a novel hypothesis to explain how the immune system recognizes intruders. Germs, he suggests, carry ancient molecular patterns that trigger the immune response. His theory and subsequent research trigger a new era of research on the “innate” immune system.

1994

The entering class of medical students is 56 percent female, the first time women have been in the majority.

1994

The FDA approves a new HIV drug developed by pharmacologist William Prusoff and senior research scientist Tai-Shun Lin. The drug, d4T (Zerit), interferes with the virus’s ability to replicate in the body. It will become part of the “cocktail” of medicines that revolutionizes HIV treatment.

2001

The school establishes a genetics center, directed by Richard P. Lifton. Over the next decade, medical school researchers will identify genes linked to numerous human diseases—from high blood pressure and kidney disease to dyslexia, macular degeneration, and Tourette’s syndrome.

2006

The school receives $57.3 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), one of 12 grants given nationwide for clinical and “translational” research—aimed at developing laboratory findings into usable treatments for patients.

2009

The Smilow Cancer Hospital, a state-of-the-art cancer care facility, opens, ensuring the future health of many cancer patients. It also ensures Yale’s status and federal funding as one of the nation’s 40 elite Comprehensive Cancer Centers. A few years earlier, crowded and outmoded clinical care facilities had earned Yale a warning from the National Cancer Institute that it might be removed from the list, and Yale officials had ramped up planning and fund-raising for construction of a new clinic.

2009

Thomas Steitz, a Sterling Professor of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, along with his two partners in analyzing the structure of the ribosome, receives the Nobel Prize.

Today

According to the most recent figures, Yale School of Medicine has 2,055 faculty, 100 MD students in the Class of 2014, 18 clinical departments, 11 basic-science departments, and 8 affiliated hospitals. It ranks fifth among medical schools in total NIH grant dollars and first in total NIH grant dollars per faculty member. U.S. News & World Report ranks it sixth among medical schools for research.  |