Last Will

How to read between the lines of the Bard’s bequests

July/August 2006

This summer, the Yale Center for British Art stages an international culture coup of Tut-like proportions. For two and a half months (through mid-September), it will have on display Shakespeare’s will—which has never before left Britain—along with the most important portraits of him, rare theatrical costumes of the period, and many other documents and artifacts of the man who was, as Sterling Professor Harold Bloom expresses it, “the greatest writer the world has ever known: unlike any writer even remotely comparable to him in stature.”

| |

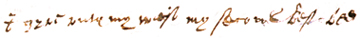

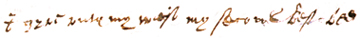

“I gyve unto my wief my second best bed.” |

The will, dated March 25, 1616, less than a month before Shakespeare’s death, is a rich trove of information—and of questions. One provision alone, Shakespeare’s bequest to his wife of his “second best bed,” has generated reams of scholarly and not-so-scholarly speculation.

To most contemporary Americans, the will is all but indecipherable. It is written in “secretary hand,” the crabbed cursive of Tudor and Jacobean England. It is full of legal formulas whose meanings are now obscure. And, as with any will, complete understanding of its contents would require intimate knowledge of the soap-opera details of the dying man’s family life. The Yale Alumni Magazine interviewed three Shakespeare experts for their insights on a document whose secrets will never be fully revealed.

Harold Bloom is Sterling Professor of the Humanities at Yale. He has published 40 books about literature.

Lawrence Manley, William R. Kenan Professor of English at Yale, writes frequently on Shakespeare and Tudor-Stuart drama.

Lena Cowen Orlin is Executive Director of the Shakespeare Association of America and Professor of English at the University of Maryland–Baltimore County.

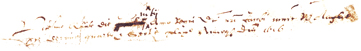

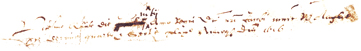

“Vicesimo Quinto die Januarii M[art]ii Anno Regni Domini nostri Jacobi nunc Regis Angliae etc decimo quarto & Scotie xlix° Annoque Domini 1616”

Lawrence Manley:

Shakespeare made his will originally in January 1616, but the final date is March 1616. His younger daughter, Judith, who had long been without a husband, got married in February to a man named Thomas Quiney—apparently in haste. They married during Lent, and marrying in Lent required a special license, which they didn’t get. (The penalty was excommunication, and indeed there is evidence that Quiney was temporarily excommunicated that spring or summer.) Quiney, meanwhile, had made another woman pregnant, and both she and the baby died that March. So things were rather a mess. It’s probably during this period that Shakespeare becomes very concerned about Judith, and that’s probably why he revised the will.

“And I doe intreat & Appoint the saied Thomas Russell Esquier & Frauncis Collins gent[leman] to be overseers hereof”

“Frauncis Collins”

Lena Cowen Orlin:

Francis Collins, Shakespeare’s lawyer, didn’t make a fair copy of his client’s will. It was written in two stages, in January and in March, and he patched the versions together. The first page is in a small, cramped hand. On the second and third pages, the handwriting is much larger. The general assumption is that the first page once looked like the second and third—but after Judith’s marriage, there was more to squeeze in. Shakespeare revised the first part in order to make sure that Judith was provided for. Collins thought he could get away without recopying all three pages, so he wrote small on the new first page in order to join it up with the old second page.

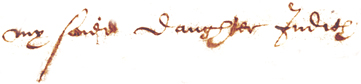

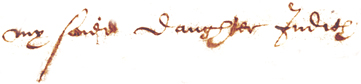

“Item I gyve … unto my saied Daughter Judyth One Hundred and Fyftie Poundes more … to be sett out by my executors … and the stock not to be paied unto her soe long as she shalbe marryed.”

“my saied Daughter Judyth”

Lawrence Manley:

Shakespeare gives Judith a hundred and fifty pounds, which is a substantial amount of money—very roughly, some sixty thousand dollars today. He also gives her the interest on another hundred and fifty pounds. But he makes sure to keep this second sum of money from Quiney—unless Quiney turns out to hang around and be a decent husband. A lengthy series of provisions concerning Judith takes up almost the entire first page. For instance, Shakespeare specifies that Judith won’t start to collect the interest until three years after the date of the will. Moreover, the money will be controlled “by my executors and overseers for the best benefit of her and her issue.” The only way her husband can get the money is to provide lands of equivalent worth to Judith and her children. So Quiney can’t touch the money at all unless he puts something in.

“Item I Gyve … unto my Daughter Susanna Hall … All that Capitall Messuage or tenemente … in Stratford aforesaid called the newe plase wherein I nowe Dwell. …”

“my Daughter Susanna Hall”

Lawrence Manley:

Susanna had married in 1607. She married a physician, who may have attended Shakespeare himself on his deathbed. This was a marriage that clearly pleased Shakespeare. The bulk of his estate, including his house, the New Place, and all the property he had purchased in Stratford beginning in the 1590s, went to Susanna. He owned a fair amount of property, including a tenement in the Blackfriars in London. That was a posh neighborhood. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men—Shakespeare’s theater company—wanted to have a theater there as early as 1596, but the neighbors made a stink about it. One of the neighbors who opposed it was the patron of the company, so it didn’t happen until 1609.

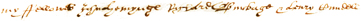

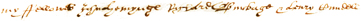

“my Fellowes John Hemynges, Richard Burbage & Henry Cundell”

Lawrence Manley:

Shakespeare makes several bequests to other relatives and people in Stratford. And then he’s written in, “to my Fellows”—the word often used by players for their theatrical colleagues—“John Hemynges, Richard Burbage and Henry Cundell, 26 shillings 8 pence apiece to buy them rings.” That’s a significant list. Burbage died in 1619. But Hemings and Condell were the two colleagues who put together the collected edition of Shakespeare’s works in 1623, “to keepe the memory of so worthy a Friend, & Fellow aliue.” So his affectionate bequest was reciprocated. For those who try to argue that Shakespeare didn’t write the plays of Shakespeare, this is a high hurdle.

“I gyve unto my wief my second best bed”

Harold Bloom:

It is the most debated bequest in literary history. The speculation arose because theirs was a shotgun marriage, as all the world knows. Susanna was born six months after the marriage was legally recorded. One can surmise, surely, that it was not a flaming love relationship. He goes off to London to seek his fortune, and he seems to have averaged several trips home a year. But whatever the difficulties had been, if they existed, the two were reconciled by the end of his life: he was living at home with her. And as impish as he could be, it is hard to believe that, in a will, one would include such a palpable irony.

Lena Cowen Orlin:

Many people find it insulting to Anne that this bequest, the sole mention of her, is added on the third page—inserted between two lines as if it were an afterthought. My theory is that it wasn’t an afterthought, but a consequence of the revision. I believe the first will was a great deal simpler, and whatever Shakespeare wanted to say about Anne was originally on the first page. There, she was probably mentioned by name. Legally, it was important to include full names for clarity, just as it was important to write not “my daughter” but “my said daughter” on second reference. This was the lawyer’s job. It may be that, with all the concern over Judith, Anne got squeezed off the first page, and the place that they found to reintroduce her was on the third page—and then Collins neglected to tidy up by specifying that she was “my wife Anne.”

There’s no emotional content in Shakespeare’s will at all, which is frustrating for us today: people want to find emotional or romantic significance—to guess the nature of his relationships. In fact, we don’t have any idea why he gave Anne Hathaway a bed. Beds appear in many wills of the time. A bed might be left to a wife because she brought it into the marriage originally as her property, or a bed might be left to a daughter because it’s the one she sleeps in. It’s likely that in Shakespeare’s family, as in many families, the best bed was reserved for guests. But one thing I do know, from all the wills I’ve read: the fact that it’s second best is not in any way pejorative or insulting. Many people left their “second-best bed”; many people also left their “worst bed.” It’s a term of identification and very common vocabulary. Somebody might leave to a single legatee a great long list of wonderful things but include in that list “my worst bed,” or “my worst cow,” or “my pot with a hole in it.”

Anne was undoubtedly provided for in some way outside the will. We don’t know if it was a marriage contract negotiated long before; or some understanding within the family; or the legal practice of “thirds,” by which one-third of the estate automatically went to the wife. In London, this practice obtained as a matter of course, without any mention in a will. We’re not sure whether the practice had the same legal force in Stratford.

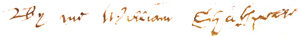

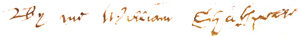

“By me William Shakespeare”

Lawrence Manley:

Shakespeare signed all three pages. On the third he signed, “By me, William Shakespeare.” Samuel Schoenbaum, author of probably the best documentary biography of Shakespeare, believes he had barely strength enough to write the last “Shakespeare.”

Harold Bloom:

The real mystery of Shakespeare, a thousand times more mysterious than any matter of the will, is: why is it that—unlike Dante, Cervantes, Chaucer, Tolstoy, whomever you wish—he makes what seems to be a voluntary choice to stop writing? In 1613 he writes somewhat less than two-fifths of The Two Noble Kinsmen; the rest is by John Fletcher. There’s something about Shakespeare’s share of it that has a strange finality. In Act 5, Scene 4, Arcite is speaking, evidently referring to Venus, Mars, and Diana. But it’s very hard not to read this as Shakespeare himself, saying goodbye to us forever:

O you heavenly Charmers,

What things you make of us! For what we lacke

We laugh, for what we have, are sorry: still

Are children in some kind. Let us be thankefull

For that which is, and with you leave dispute

That are above our question. Let’s goe off,

And beare us like the time.

Except for a bit of doggerel for his tomb—“Cursed be he who moves my bones”—these are the last lines Shakespeare ever writes.  |